A brief history

The Shell Centre was founded during 1967, largely as a result of the efforts of the Professors of Pure and Applied

Mathematics in the University of Nottingham, Heini Halberstam and George Hall. They persuaded the Vice Chancellor,

Sir Frederick Dainton, of the importance of the post-Sputnik international effort to improve the teaching

of mathematics in schools. Some mathematicians at that time believed that the keys to improvement were a

deeper understanding of the subject by teachers and a focus on fundamentals in teaching. Dainton in turn

persuaded the leadership of Shell UK Ltd to fund the Centre for four years as an “extra-faculty research

unit”. Three full-time lecturers were appointed: Alan Bell, Robert Lindsay and Ruth Tobias, later replaced

by David Hale. Their brief was to lead professional development activities across the East Midlands, as well

as continuing their various national roles.

The Centre was seen as successful so the University persuaded the University Grants Committee that the Centre’s

funding should be included in the University’s block grant from government for the 1972 quinquennium, and

a chair was added. Vernon Armitage became Professor of Mathematical Education in the Mathematics Department

and Director of the Shell Centre. His broad background combined teaching at Shrewsbury School, advising the

School Mathematics Project, and research in number theory. The work of the Centre continued to focus on professional

development activities, building close links with David Sturgess and other mathematicians in the School of

Education. In parallel, Alan Bell worked with the heads of mathematics in two local schools, David Rooke

and Alan Wigley, to develop Journey into Maths – teaching materials for students aged 11-14 that included

a strong investigative element. When in 1975 Professor Armitage decided to return to the University of Durham,

Nottingham again sought a successor with a background in both mathematical research and work with schools.

Hugh Burkhardt was appointed. A theoretical elementary particle physicist, he had since 1963 pioneered the teaching

of mathematical modeling – to undergraduates and to teachers in professional development workshops. Far from

convinced that we know how best to teach mathematics, he negotiated with the University a broader brief:

“to work to improve the teaching and learning of mathematics regionally, nationally and internationally”.

The vision was, and is, to focus on research, design and development that will have direct impact on what

happens in school mathematics classrooms.

He saw various things as central. With a team of just four permanent staff, he decided that any large-scale influence

could only be achieved through reproducible materials that support more effective teaching. Since teachers

are busy people and change inevitably involves extra demands, it was and is crucial to find levers in the

education system that will encourage teachers and other professionals to make the substantial effort needed.

He saw people’s lack of confidence in and enjoyment of mathematics as a curriculum failure; encouragingly,

there were rich and interesting mathematics materials that contrasted with the procedural nature of most

mathematics textbooks, and lessons. This suggested an important role for imaginative design.

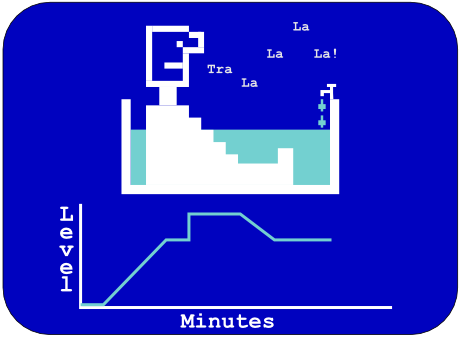

Thus the late 1970s began an ongoing search for outstanding designer-researchers. The new opportunities that

computer technology offer led to a collaboration with Rosemary Fraser’s group in Plymouth, developing her

original and powerful approach based on a single ‘computer + television display’ per class. This brought

talented people into the Centre including, notably, Richard Phillips, Daniel Pead, Rita Crust and Rosemary

herself. The key appointment of Malcolm Swan in 1979 developed gradually into his design leadership of many

of the Centre’s projects and, ultimately, his becoming Director.

Thus the late 1970s began an ongoing search for outstanding designer-researchers. The new opportunities that

computer technology offer led to a collaboration with Rosemary Fraser’s group in Plymouth, developing her

original and powerful approach based on a single ‘computer + television display’ per class. This brought

talented people into the Centre including, notably, Richard Phillips, Daniel Pead, Rita Crust and Rosemary

herself. The key appointment of Malcolm Swan in 1979 developed gradually into his design leadership of many

of the Centre’s projects and, ultimately, his becoming Director.

The “design research” style of working, developed through the 1980s and since, is based on input from prior research

that informs creative design. In the absence of a research-based industry in education, the team does its

own systematic product development – hence “engineering research in education”. This involves rapid prototyping

(“Fail fast, fail often”) and an iterative process of classroom trials and revision, informed by rich detailed

feedback from skilled observers on what happens.

The team introduced various novel features. For example, "WYTIWYG" – high-stakes examinations strongly influence

what happens in classrooms (what you test is what you get) so the team has often collaborated with test providers

– from the Testing Strategic Skills and Numeracy through Problem Solving projects with the Joint Matriculation

Board in the 1980s to the recent US-based Mathematics Assessment Project. These explicitly recognized “the

few year gap” between recently learned mathematics and the maths that people can use in tackling non-routine

problems. The multi-dimensional nature of task difficulty was articulated in MAP as “novice”, “apprentice”

and “expert” tasks: successively more strategic and less technical in their demands.

The team introduced various novel features. For example, "WYTIWYG" – high-stakes examinations strongly influence

what happens in classrooms (what you test is what you get) so the team has often collaborated with test providers

– from the Testing Strategic Skills and Numeracy through Problem Solving projects with the Joint Matriculation

Board in the 1980s to the recent US-based Mathematics Assessment Project. These explicitly recognized “the

few year gap” between recently learned mathematics and the maths that people can use in tackling non-routine

problems. The multi-dimensional nature of task difficulty was articulated in MAP as “novice”, “apprentice”

and “expert” tasks: successively more strategic and less technical in their demands.

One continuing strand of linked research and development has been Diagnostic Teaching, a specific and powerful

form of formative assessment for learning. Initiated by Alan Bell and taken forward by Malcolm Swan, it has

developed from a series of small research studies in the 1980s through a sequence of projects, culminating

in the Mathematics Assessment Project – where over 7 million lesson downloads illustrate its impact.

One continuing strand of linked research and development has been Diagnostic Teaching, a specific and powerful

form of formative assessment for learning. Initiated by Alan Bell and taken forward by Malcolm Swan, it has

developed from a series of small research studies in the 1980s through a sequence of projects, culminating

in the Mathematics Assessment Project – where over 7 million lesson downloads illustrate its impact.

Around the year 2000, we saw the need for a formal association of researcher-designers. Working with others around

the world we established ISDDE, the International Society for Design and Development in Education, with the

goals of working as a community to improve the quality of engineering research in STEM education – and its

influence on policy. Now with over 100 Fellows and Members, ISDDE meets annually in places around the world.

The Shell Centre’s official status within the University of Nottingham has changed several times. During the

1980s, the “block grant principle” for funding universities gave way to a business model in which income

and expenditure streams became ever more closely aligned. A research centre with five staff and fewer students

had to change. In 1989 two things came together: the need to raise outside research funding to cover all

the Centre’s costs and generous early retirement offers to the senior staff. Hugh Burkhardt, Alan Bell and

Rosemary Fraser accepted the offer on the understanding that they could continue to work on projects for

which they raised external funding, while Malcolm Swan and Richard Phillips formally joined the staff of

the University’s School of Education. On this basis the team has succeeded in first surviving, then expanding

through a program of work that is widely admired around the world. It gradually merged into the School, while

retaining the operational independence that external funding allows. In 2008 Malcolm Swan became Professor

and Director of a broader Centre for Research in Mathematics Education with the Shell Centre team at its

heart. He was succeeded in 2015 by Geoff Wake. “The Shell Centre” is now a brand that epitomizes engineering

research in education, and continues to attract support for projects like those on which its reputation was

built.

The Shell Centre’s official status within the University of Nottingham has changed several times. During the

1980s, the “block grant principle” for funding universities gave way to a business model in which income

and expenditure streams became ever more closely aligned. A research centre with five staff and fewer students

had to change. In 1989 two things came together: the need to raise outside research funding to cover all

the Centre’s costs and generous early retirement offers to the senior staff. Hugh Burkhardt, Alan Bell and

Rosemary Fraser accepted the offer on the understanding that they could continue to work on projects for

which they raised external funding, while Malcolm Swan and Richard Phillips formally joined the staff of

the University’s School of Education. On this basis the team has succeeded in first surviving, then expanding

through a program of work that is widely admired around the world. It gradually merged into the School, while

retaining the operational independence that external funding allows. In 2008 Malcolm Swan became Professor

and Director of a broader Centre for Research in Mathematics Education with the Shell Centre team at its

heart. He was succeeded in 2015 by Geoff Wake. “The Shell Centre” is now a brand that epitomizes engineering

research in education, and continues to attract support for projects like those on which its reputation was

built.

In 2016 the team's achievements were recognized by the International Commission on Mathematical Instruction when

Hugh Burkhardt and Malcolm Swan became the first recipients of the Emma Castelnuovo Award. The citation includes:

"Burkhardt and Swan have served as strategic and creative leaders ofthe Nottingham-based Shell Centre team of

researcher-designers. That team has included many talented individuals over nearly 4 decades, in parallel

with the contributions of more recent teams of international collaborators. Burkhardt and Swan are selected

because of their continuous leadership of this work. Together, they have produced groundbreaking contributions

that have had a remarkable influence on the practice of mathematics education as exemplified by Emma Castelnuovo."

Thus the late 1970s began an ongoing search for outstanding designer-researchers. The new opportunities that

computer technology offer led to a collaboration with Rosemary Fraser’s group in Plymouth, developing her

original and powerful approach based on a single ‘computer + television display’ per class. This brought

talented people into the Centre including, notably, Richard Phillips, Daniel Pead, Rita Crust and Rosemary

herself. The key appointment of Malcolm Swan in 1979 developed gradually into his design leadership of many

of the Centre’s projects and, ultimately, his becoming Director.

Thus the late 1970s began an ongoing search for outstanding designer-researchers. The new opportunities that

computer technology offer led to a collaboration with Rosemary Fraser’s group in Plymouth, developing her

original and powerful approach based on a single ‘computer + television display’ per class. This brought

talented people into the Centre including, notably, Richard Phillips, Daniel Pead, Rita Crust and Rosemary

herself. The key appointment of Malcolm Swan in 1979 developed gradually into his design leadership of many

of the Centre’s projects and, ultimately, his becoming Director.

The team introduced various novel features. For example, "WYTIWYG" – high-stakes examinations strongly influence

what happens in classrooms (what you test is what you get) so the team has often collaborated with test providers

– from the

The team introduced various novel features. For example, "WYTIWYG" – high-stakes examinations strongly influence

what happens in classrooms (what you test is what you get) so the team has often collaborated with test providers

– from the  One continuing strand of linked research and development has been Diagnostic Teaching, a specific and powerful

form of formative assessment for learning. Initiated by Alan Bell and taken forward by Malcolm Swan, it has

developed from a series of small research studies in the 1980s through a sequence of projects, culminating

in the

One continuing strand of linked research and development has been Diagnostic Teaching, a specific and powerful

form of formative assessment for learning. Initiated by Alan Bell and taken forward by Malcolm Swan, it has

developed from a series of small research studies in the 1980s through a sequence of projects, culminating

in the  The Shell Centre’s official status within the University of Nottingham has changed several times. During the

1980s, the “block grant principle” for funding universities gave way to a business model in which income

and expenditure streams became ever more closely aligned. A research centre with five staff and fewer students

had to change. In 1989 two things came together: the need to raise outside research funding to cover all

the Centre’s costs and generous early retirement offers to the senior staff. Hugh Burkhardt, Alan Bell and

Rosemary Fraser accepted the offer on the understanding that they could continue to work on projects for

which they raised external funding, while Malcolm Swan and Richard Phillips formally joined the staff of

the University’s School of Education. On this basis the team has succeeded in first surviving, then expanding

through a program of work that is widely admired around the world. It gradually merged into the School, while

retaining the operational independence that external funding allows. In 2008 Malcolm Swan became Professor

and Director of a broader Centre for Research in Mathematics Education with the Shell Centre team at its

heart. He was succeeded in 2015 by Geoff Wake. “The Shell Centre” is now a brand that epitomizes engineering

research in education, and continues to attract support for projects like those on which its reputation was

built.

The Shell Centre’s official status within the University of Nottingham has changed several times. During the

1980s, the “block grant principle” for funding universities gave way to a business model in which income

and expenditure streams became ever more closely aligned. A research centre with five staff and fewer students

had to change. In 1989 two things came together: the need to raise outside research funding to cover all

the Centre’s costs and generous early retirement offers to the senior staff. Hugh Burkhardt, Alan Bell and

Rosemary Fraser accepted the offer on the understanding that they could continue to work on projects for

which they raised external funding, while Malcolm Swan and Richard Phillips formally joined the staff of

the University’s School of Education. On this basis the team has succeeded in first surviving, then expanding

through a program of work that is widely admired around the world. It gradually merged into the School, while

retaining the operational independence that external funding allows. In 2008 Malcolm Swan became Professor

and Director of a broader Centre for Research in Mathematics Education with the Shell Centre team at its

heart. He was succeeded in 2015 by Geoff Wake. “The Shell Centre” is now a brand that epitomizes engineering

research in education, and continues to attract support for projects like those on which its reputation was

built.